Especially For You- Finding a New Purpose after Unspeakable Loss

A work of narrative nonfiction by Ken Brack

I needed to weave their stories together in order to make any meaning of our own.

First excerpt: "You can do this"

Second excerpt: "This defiance for peace"

Third excerpt: "All right to hurt"

Fourth excerpt: "Reciprocity of gratitude"

Fifth excerpt: "His fiddle told the story"

Annotated contents of the main sections:

Preface

In the predawn hours of November 15, 2002, every parent’s worst nightmare strikes the author and his wife, who learn that their son has died in a car crash along with a friend. Restless and sometimes combative, loved by his buds and family, Mike was just eighteen and beginning to figure things out. As the author, a longtime journalist and aspiring teacher, reaches the state police, his gut tells him that their lives will never be the same. The couple has joined a club that no one signs up for.

Part I - Into the rip

Why me? What do I do now? How do I heal this hole in my heart? The questions are ageless and yet raw whenever catastrophe or tragedy strikes.

While this book weaves together striking accounts of staggering loss, it is more about what comes next. Less concerned with why many of us finally get off the couch, the focus is on how we may find a new purpose while wrestling with those stubborn existential questions.

Labyrinth shards illustration by Amanda Brack

During an age when resiliency is often celebrated—frequently in the aftermath of mass shootings and terror attacks—less well understood is how people actually make something positive from their trials, and how this differs from perseverance. As relatives and friends of lost loved ones plunge back into the same forces that ripped open their lives, this response often exacts an extraordinary cost. Sparked by one of his high school student’s questions to a Holocaust survivor, the author sets out interviewing a select group of families, seeking inspiration from how they attempted to move forward from sudden loss and other trauma. The breadth of the work is introduced, addressing primarily adults looking for answers to painful ordeals and ways to support friends and loved ones, and a more general audience intrigued by transformative accounts in a hybrid of narrative, reportorial, and creative nonfiction.

What inspired me most were those who found a way forward by giving back.

Part II: Wrenched open

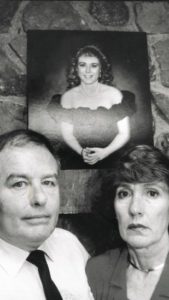

What do you do when your daughter has been raped and murdered in her freshman dormitory bed? As the world turned upside down for Jeanne Clery’s parents in 1986, they discovered that her university had hid many earlier violent campus crimes. Hoping to prevent other families from suffering the same, the Clerys began advocating for greater accountability and campus safety protocols, forming a nonprofit group to help enact reforms across the country.

What do you do when your daughter has been raped and murdered in her freshman dormitory bed? As the world turned upside down for Jeanne Clery’s parents in 1986, they discovered that her university had hid many earlier violent campus crimes. Hoping to prevent other families from suffering the same, the Clerys began advocating for greater accountability and campus safety protocols, forming a nonprofit group to help enact reforms across the country.

While struggling to reconcile Jeanne’s death and reclaim their faith, her parents joined with other families and advocates to become vanguards advancing the rights of student crime victims. More than a quarter century later, Jeanne’s mother continued to lay down the challenge after setting a foundation for today’s survivors of campus sexual assaults, some of whom continue to break the silence for others.

Part III. A way forward

A reciprocity of gratitude may be the most endearing result of 9/11.

Many Americans recall exactly where they were during the 2001 terrorist attacks. Iconic images of our initial responses periodically rekindle national unity and shared resolve. Yet while 9/11 families have not been forgotten, their trials including those of first responders’ relatives often went unnoticed as more than a decade passed. Some of the victims’ relatives and friends took steps forward from their loss by doing acts of service while paying tribute to the fallen.

Many Americans recall exactly where they were during the 2001 terrorist attacks. Iconic images of our initial responses periodically rekindle national unity and shared resolve. Yet while 9/11 families have not been forgotten, their trials including those of first responders’ relatives often went unnoticed as more than a decade passed. Some of the victims’ relatives and friends took steps forward from their loss by doing acts of service while paying tribute to the fallen.

This section chronicles the responses of two people and their families, both of whom connected with like-minded individuals striving to sustain the compassion that may be the most endearing result of 9/11. First, a volunteer firefighter who rushed into the South Tower to do triage inspired his brother and a friend to encourage millions of others to give back. This led to the creation of the September 11th National Day of Service and Remembrance. Second is the story of a widow’s resolve to “pay it forward” along with caring for her traumatized sons after their dad was killed at work in the North Tower. The experiences of other families and friends of the firefighter are woven through.

Part IV. The depths of healing

Sam, Nathan, and Bernard Offen lost almost everything during the Second World War: their family, neighborhood, and country. Their humanity was severely tested in Nazi-occupied Kraków and various concentration camps. Eventually each one decided to become a witness to the world after taking disparate paths to face his past.

As this section begins, oldest brother Sam hugs an Army veteran from Detroit, one of his liberators at Mauthausen; middle brother Nathan goes skydiving in Florida for his ninetieth birthday; while younger Bernard completes a walking tour of Auschwitz and Kraków, where he spends each summer guiding people through the former camp and ghetto in what he calls a self-determination process of healing. While very different–Sam bubbles with optimism, Nathan is reticent and hard-boiled, and Bernard veers from being caustic to mystical–the arcs of their lives, and their contributions, are singular. Their survival is less a testament to idealized resilience than to the complex struggle to reconcile harrowing trauma.

Part V. The cost

How do we begin to reconcile the past while moving forward?

Nathan and Helen Offen at their engagement party in London, 1950 (third and fourth from left). Nathan's brothers Sam and Bernard are in the top row, third and fourth from left. Photo courtesy of Stephen Freedman.

What is the cost of not simply letting go, and plunging yourself into the very forces that ripped open your life? Or the opposite: running away from and numbing that place of pain? How do people to find balance between the two, and begin to reconcile the past while moving forward?

Spurred by the poor decisions that his son Mike and friends made in 2002—and fueled by his anger while uncovering the seedy, underage drinking scene in Providence, Rhode Island, where the four indulged one mid-November night—the author attempts to confront the cause of tragedy and channel his wrath. Contemplating the limits of forgiveness and seeking redemption, the Bracks attempt to reconcile with the driver, believing that is what their son would want. Also included are the voices of two parents who lost their only son in Iraq in 2005 and struggle to hold him close amidst a custody battle for their grandson, and a FDNY veteran who fled New York, knowing his fallen brothers “are with me every day.”

Part VI. Unspeakable gifts

The author’s wife Denise envisions opening a bereavement center to support other families going through similar crises, which necessitates a huge shift and difficult balance in their lives. Opening a nonprofit requires them to step beyond their anguish to lift others in their grief. After setting out in 2008, Denise Brack builds key partnerships and formalizes facilitator training for support groups while seeking space to replenish her emotional energy.

The author’s wife Denise envisions opening a bereavement center to support other families going through similar crises, which necessitates a huge shift and difficult balance in their lives. Opening a nonprofit requires them to step beyond their anguish to lift others in their grief. After setting out in 2008, Denise Brack builds key partnerships and formalizes facilitator training for support groups while seeking space to replenish her emotional energy.

As their nonprofit grows, pressures mount to continue Hope Floats Healing & Wellness Center’s operations. Expecting to expand this outreach to a wider community, the Bracks realize they must keep their hearts open to intuition and a life of service, while recognizing that facing one’s pain rather than shuttering it is a lifelong trek towards reclamation. Their family experiences luminous moments of remembrance and solidarity, receiving signs from Mike and recognizing his ongoing connection to them. Mike’s core friends also demonstrate the strength of their own bonds, which along with the contributions of Denise’s colleagues and friends, are an unspeakable gift.

Denise and Ken Brack in November 2012, during a celebration of their son Michael's life on his tenth anniversary.

First excerpt from Especially For You

You can do this.

Jeff Doyle recalls the guys stretching out beside the track, freshmen with quaking nerves and some with long faces knowing they would not make it. And select dudes strolling in with their headphones on.

Mike immediately stripped off his shirt. “He’d enjoy that, even without any girls around,” Doyle was telling me. “He had that six pack, that jacked body,” those ripped abs. “And telling people he had his shirt off.” He just had that body.

Jeff laughs gazing back for a moment. We’re in the kitchen at Hope Floats, the guts of the old house. Maybe Edward and his daughters are listening in; one of the girls enjoys flirting with Mike’s spirit, after all, the kid in Adidas flip-flops. Doyle says he doesn’t distinguish among most of his former players. Matches and records and other stats kind of glaze into one, even some of the names.

But not the morning of The Deuce.

Doyle was a talented player himself, a member of Silver Lake’s state championship team in 1988, and then a captain on the Southern New Hampshire University squad, which won an NCAA Division II National Championship the following year. In college he had to pass the “Cooper test,” running two miles in twelve minutes, his best time coming as a freshman at 11:25. When he became head coach at Silver Lake Regional High School in the late nineties, Doyle introduced the same training standard to all of those vying for a spot.

Someone had dubbed it “The Deuce” by the time Mike arrived for double sessions late one summer.

Mike just took his shirt off and flew.

It was usually a Thursday morning, and just after checking the boys’ paperwork, Doyle began assigning them to line up for the heats. There was no prescribed training for it other than an outline he issued during the spring meeting. Coach Doyle advised them to alternate their running, perhaps doing three, then five, to seven miles, rather than going out just doing two miles faster and faster. “I always told the kids, it’s a measure of fitness. It’s a measure of what you’ve got.” They needed a goal for the summer.

Failure to pass did not mean they were ineligible or off the team, despite the popular fear that careened through kitchens and dens like our own. They might not start, or play a full game. Doyle often made them repeat. He applied the benchmark unevenly, sometimes retaining starters like big, slower backs whom he just wanted on the field. Mike was cool in front of his friends, a bit snappy at home with us. He didn’t want to have to run it again.

The guys psyched each other up body smacking with light punches and trash-talk. A few savvy ones grouped with older guys who’d already been successful and knew what pace to set. Others tried talking themselves into it. Coming into the eighth lap, those on the sidelines roared, with some running alongside the track urging a teammate to finish. You can do this. Balls to the wall.

Mike just took his shirt off and flew.He unleashed that Tasmanian devil energy. He had something of his mom’s gazelle legs and track-running stock, and probably some of my bent to get lost in the run and go harder.

Coming into his junior year, he passed at 11:44, among the top four.

He tied with Harrison Walters, whom Doyle called the “H-bomb,” having devised as a non-strategy that if the game were in doubt, they’d kick the ball as far as possible hoping speedy Harrison would get to it first.

During senior year Mike finished in the top three with his best buds. He came in at 11:34, behind Jeff at 11:30. Travis, despite puking on the track, was first at 11:27.

“Some guys would do the best they ever did with all the support and camaraderie,” Doyle says before chuckling again. “It was great. Still, and then they had to go out and practice after that.”

This response, this defiance for peace, is really interesting. -- David Paine

In 2015, David Paine and Jay Winuk found themselves being led by children—fourteen year-olds who were born on September 11, 2001.

Participation had continued to grow marking the anniversary of 9/11 with acts of service and kindness, yet they realized that one-quarter of the country had no memory of the attacks. To connect with younger generations and sustain the movement, they would need to tap into something larger. “The motivation has to be deeper and broader than paying tribute to those who lost their lives,” David told me as he and Jay sowed new seeds for the fifteenth-year commemoration.

More than thirteen thousand babies arrived across the United States on 9/11, and Paine wondered whether some of those adolescents found the day important. After reaching out to them in the summer of 2015, nearly two dozen teens shared their idealism in interviews. Hillary O’Neill, a middle school student in Norwalk, Connecticut knew families who lost relatives.

O’Neill’s hope was that her birthday would become a day when people observe how much the world has changed. “How it transformed,” she anticipated, speaking in a video done for 911day.org. “If we all do good deeds on 9/11, it will all add up.” She set up a lemonade stand to raise money for a charity.

Such enthusiasm helped Paine and Winuk rebrand their campaign as“Hope was born on 9/11.”

“They want the world to be better,” David said, “and they agree with the day as a concept in itself. The day is about making things better.”

Volunteers packing food boxes carry forward spirited service during the 15th anniversary of 9/11. Courtesy of 9/11Day

On the anniversary, some of the teens helped package meals at a City Harvest food bank alongside adults in New York who had experienced the attacks. The kids fit right in, and David found it was less their physical involvement than how they touched others around them. “They so perfectly communicated the message that there is goodness that came out of 9/11,” he said.

Every few years, Paine found himself tweaking the 9/11 day’s engine, perhaps cleaning a dirty carburetor to stop the rough idling. He and Jay considered handing it off to O’Neill’s generation—and the next.

The anniversary could become a moment to express their hopes. “A moment when they can stop and ask their friends to support them,” David said. “Whatever the cause is—it could be about peace, or poverty, or hunger—all those things. They just a need a day that can be theirs.”

We want to find ways to express our remorse in a constructive fashion.

Paine stands on Vesey Street again, this time within view of the gleaming new One World Trade Center, soon to be the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere. On this chilly April morning he is back downtown with Jay at a 5K tribute run for 9/11 families. Just six days earlier, the attacks at the Boston Marathon finish scared the bejesus out of many of us.

“I think we’re all kindred spirits,” Paine is saying. “We want to find ways to express our remorse in a constructive fashion, and that whenever we see something, we link to it somehow. It seems to be an emerging movement that is sparked by hate.

Volunteers sign a Tribute board during the 9/11 anniversary. Courtesy 9/11 Day

“This response, this defiance for peace, is really interesting,” he continues. “The fact that we’re dealing with it showing sensitivity and compassion, and caring for one another . . .”

He trails off momentarily. Reaction to the bombing in Beantown surrounds us. Many runners carry expressions of solidarity for their usual division rivals. A band performs “Sweet Caroline,” the emblematic seventh-inning stretch sing-along of the Red Sox. Paine finishes with, “. . . what Boston just did—they learned that from the 9/11 tragedy.”

Perhaps. But where will everyone be six or sixteen years out?

The previous December, Paine was on a treadmill in Newport Beach when CNN reported the Newtown shootings. Running into the bedroom to find his wife, David was crying again. He started an online sympathy card, wanting to reach out in an offer of psychic healing, something, anything, starting with MyGoodDeed’s mailing list. He went out for lunch and came back and there were seventy thousand signatures in about two hours. Which is ridiculous. It became the fastest-growing petition ever on the Causes.com platform, and within a week he gathered 2.5 million signatures from 140 countries.

David flew east and drove out with his sister. They presented a facsimile of the card with the first twenty thousand signatures the following Friday to Newtown’s selectmen, gathering at a soccer field for a vigil attended by two thousand people. Jay jumped in as well. Meeting neighbors who rallied to support the victims’ families, both Winuk and Paine helped them organize a nonprofit and prepare their message to kickoff a campaign, advocating for common sense, anything, to address the complex forces that enable the Adam Lanzas to do such incalculable harm.

One of those neighbors, Lee Shull, a software consultant who lives down the street from two of Lanza’s victims, finishes running with his son along the Hudson River during the 9/11 family event. His wife and twin daughter have also walked the route, now squeezing down the closed-off road between a kids’ play area and food vendors alongside firemen doing a recruiting drive. The group Shull helped start, Sandy Hook Promise, seeks middle ground to address gun violence and improve mental health supports and school safety. It really just stemmed out of a need, a need to a need to do something, and a feeling that this could happen anywhere.

A need to do something.

We have a purpose.

We're not going to shrink.

There’s a solidarity binding Lee Shull with David and Jay and so many others that transcends how we often define empathy. An infectious leap, a roar, to right a wrong. “We came to the realization that we can’t live our lives in fear,” Shull says. “It’s just not a sustainable way for us to live. We’re not going to shrink.”

Winuk has the marathon response on his mind, in addition to Newtown.

“It just seems to bring out the best of people,” Jay says. “People rise to the occasion, and that is very promising and empowering, and soothing, and healing.”

He and David have a book to write, a modern epic. If they can ever sequester themselves long enough.

Third excerpt:

All right to hurt

Howard and Connie Clery also did a lot to preserve Jeanne’s memory at her high school, donating a pointed fieldstone fountain and landscaping with English garden benches. They established a scholarship for students in financial need and furnished new bleachers for the tennis courts beside a memorial stone that reads, “Her laughter will always live in our hearts.”

There were other plaques, a memory garden, and a class night award. Each of these things would auger deep into their conception of what is bittersweet. Each would inevitably gather dust and even hint at feeling perversely ubiquitous, blending over time with other families’ attempts to preserve another loved one’s legacy.

There were other plaques, a memory garden, and a class night award. Each of these things would auger deep into their conception of what is bittersweet. Each would inevitably gather dust and even hint at feeling perversely ubiquitous, blending over time with other families’ attempts to preserve another loved one’s legacy.

At some point, the Clerys would need to skip the lengthening scholarship ceremonies. In the best case, their daughter’s closest friends and others who mattered most would retain their connections with Jeanne, distilled from what once was the clarity of her presence. Even as the sharpness faded, her essence remained: “Truly a fighter and a hard worker, just a nice solid athlete, and a good kid,” her tennis coach summed up. Memory continued to believe, even if holding on to threads.

Back home, Jeanne’s father developed a routine with Sister Miriam, a Lebanese-American nun who conducted their Bible study group. He invited her to their house, and during those first six months or so, five and even six times a week Miriam drove over during the afternoons.

You only feel pain because you love.

Both parents greeted her at the door, and after offering her a cold drink Connie left Miriam and her husband alone. He vented, often for two hours, and she cried along with him. But mostly she listened. Each disclosure stabbed at him: Lehigh’s knowledge of doors propped open; the access to dormitories Henry had through his university job; the denials of responsibility.

“For Connie and Howard it was like throwing acid on raw skin,” she says. Howard often repeated himself in their sessions together, which she found to be so necessary.

He needed to know it was all right to hurt. He needed to know it was all right to sob his heart out. He needed to know it was perfectly normal and justified that he would feel so much anger, so much confusion and desire such ravenous revenge. “He needed to know,” she recalls, “it was okay to feel that. Because some people believe you can’t feel that way, it’s a sin.”

You only feel pain because you love.

Miriam and Howard already had an indelible connection. She was a member of the Daughters of the Heart of Mary, a religious order founded in secrecy during the French Revolution. To avoid persecution under Robespierre’s Reign of Terror, its members avoided external identifications of their faith, and they continue this practice today. They do not wear habits, assume titles, or live in a convent. They often work as doctors, teachers, or social workers, and conduct retreats around the world and missions in places including the Bronx and Atlantic City.

Miriam Najimy believes Divine Providence led her to make her vows after what she describes as years of devastating lows. She struggled growing up with a severe speech impediment and teachers told Miriam’s parents that she was borderline retarded but should stay in school—just in case.

“I believed it and they believed it, and I never saw much of a future for myself,” she says. Howard marveled at how this petite woman overcame her disability and embraced a theology that was so grounded, and unvarnished by ritual.

Mostly, they searched.

At age eighty-two she was vigorous and spry, a member of an assisted living residence for retirees of her order. Her brown eyes were warm and she relished learning new things. She offered a clarity of redemptive wisdom, an affirmation of what she called “how to live as authentic human beings.” People of great faith doubted they even had it, she told me. They railed, they drove loved ones away. They even numbed themselves.

But mostly, they searched.

Howard, she said, was constantly searching and learning. Even before losing Jeanne he argued that God was unjust, or absent, during genocide, wars, and famine—not uncommon questions, which she found perfectly valid. As he prepared to challenge their study group, eyes would roll again throughout the room. “Will we ever get the answer? I don’t know that we ever will, on this side of eternity,” she says. “And when we reach the other side of eternity, will it matter? I don’t know.”

Over those months and the seasons ahead, Sister Miriam affirmed Howard Clery’s questions and pain. She observed how he and Connie were living among that full canopy. “This thing they call Catholic guilt— you’re not supposed to feel this way—that’s a bunch of nonsense,” she says.

Over those months and the seasons ahead, Sister Miriam affirmed Howard Clery’s questions and pain. She observed how he and Connie were living among that full canopy. “This thing they call Catholic guilt— you’re not supposed to feel this way—that’s a bunch of nonsense,” she says.

“When you hurt you need to cry out.”

The specter of Josoph Henry hovered close by, snapping the family back in a whiplash with each of his court appeals.

Fourth excerpt:

A reciprocity of gratitude

On May 29, 2002, a construction worker who had struggled to believe in God stood in the sanctuary at Saint Paul’s Chapel, across from Ground Zero.

Tom Geraghty lost his sister-in-law in the attacks, and for months afterward, like scores of others, he found refuge in the colonial-era church. George Washington prayed there after his inauguration, and Saint Paul’s somehow escaped damage on 9/11, even when a steel beam from the North Tower toppled a massive sycamore in its yard, the graves at the edge not thirty feet away from rubble. By one account the church was spared destruction from the blasts by the innocence of some homeless men who spent the night on cots in the organ loft shelter. They cracked open a window to get some air, forgetting to close it as they left early Tuesday morning, and that opening provided a pathway to relieve some of the thundering pressure.

Within a few days something remarkable started to happen.

St. Paul's Chapel, beside the World Trade Center. Henny Ray Abrams/AFP/Getty Images)

The chapel was transformed into a rescue center and stayed open continuously 260 days for rescue and recovery workers desperate for food, sleep, even a momentary slice of grace. Volunteers provided water and coffee, more cots, foot massages and counselors, while some of the same men from the shelter grilled burgers. Firefighters grabbed a couple of hours in a pew. Some half million meals were served.

It took a few days to actually open up since the building had to be declared safe by city inspectors. On September 12 the associate minister, the Reverend Lyndon Harris, walked down from Greenwich Village, not expecting to see the church spire. “The place so eerie, yet so filled with spiritual energy, was covered with soot, but it was almost as if sparks were flying off my boots as I walked in,” Harris recalled. “It was clear to me that we were spared, not because we were holier than anybody who died across the street, but because we had a big job to do.”

By September 13 people were digging out paper and dust in the cemetery, and the next day at noon, workers at the pile stood up, astonished, when the church bell rang out twelve times. Saint Paul’s became a restorative enclave with daily celebrations of the Eucharist reserved for rescuers. By the next spring nearly every surface in the sanctuary was covered in banners and well wishes from around the world. Geraghty and others, EMTs, port authority workers and city police and firemen thanked the church, which was officially closing its mission that morning.

This circle of gratitude is infectious. I hope it turns into an epidemic. -- Rev. Lyndon Harris

Reverend Harris noted in his homily that through three seasons of trying to restore order from chaos and reclaim their humanity, what emerged was “a season of renewal.” He continued, “Ultimately, what began in hatred has evolved into, in the words from that great song in the musical Rent, a season of love.” Drawing from Matthew 25, he urged the crowd “to be a community that exists, not for itself, but for the sake of others.”

Thanking the more than five thousand volunteers, he then offered: “Emerging here is a dynamic I like to refer to as a ‘reciprocity of gratitude’—a circle of thanksgiving—in which people have risen to the scriptural challenge…’to try and outdo one another in showing love.’ Both giver and receiver have been changed by it. This circle of gratitude is infectious. And I hope it spreads. I hope it turns into an epidemic.”

That reciprocity is the baton that David Paine and Jay Winuk grabbed hold of.

Glenn’s friend Dan King felt it, too. In those first weeks he worked at Ground Zero even on his days off. The flood of volunteers, their compassion for rescuers and officers, and for each other, almost overwhelmed him. “I’d go down there, all these people who were volunteering and handing things out, food, and they’re thanking us. I’m looking at them and saying, ‘Thank you, look at what you’re doing.’ I spent a lot of time crying in my car on the way in and on the way home. For a long time I just couldn’t sit still.”

Neither was it easy for King’s family. His son Ryan struggled to understand what had happened. He’d been given a birthday cake in class that Tuesday, but the adults around him were in tears, parents pulling his friends out of school. Ryan even wrote a letter that his dad kept hanging on his office wall for at least a decade. His fifth-grade class made an American flag out of handprints, and King and another parent, a city firefighter, had an idea. Rather than hang it at the firehouse in their hometown of North Merrick, they brought it to Ten House.

In the years ahead, King tried to instill those values that Glenn lived by in each of his three sons. “I tell them, ‘Lead by example.’ I try to keep his memory alive by trying to do the right thing—by being true and honest.”

One morning I walked Glenn’s possible routes from his office to the trade center. If he had gone one way he’d have passed Saint Paul’s to his right and come down beside its gently sloping burial ground. To me, the church stood like a defiant sentinel amidst the crimes of humanity, pressed against the crucible of those draining months, and resuming its watch over the swells of people who press forward and aft through the financial district every working day. But Glenn’s co-workers and friends insist he took another, more direct way, exiting his building to Dey Street. I continued in that direction and then toward the firefighters’ memorial wall.

It was five days after Christmas, and reaching the corner of Greenwich and Liberty streets shortly after daybreak I came upon a small balsam fir, not seven-feet-tall, decorated with men’s photos and prayer cards. I took another step and there was Glenn Winuk’s memorial affixed to a large marble slab. I took a while there and offered a prayer to the Winuks, and to all the families who lost loved ones and continue to suffer from the attacks.

A cluster of small candles remained burning on the sidewalk. The air was still, strangely hushed, other than the beeping of a loader and other heavy equipment across the street.

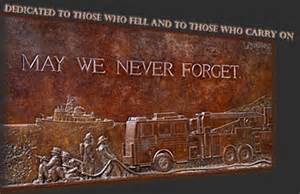

Beside Glenn’s plaque begins the FDNY Memorial Wall. I followed the mural slowly from left to right, panning the expressions on the etched faces, their language silent, evocative. I read the dedication and felt complete accord: “To those who fell and to those who carry on. May we never forget.”

A worker on the corner, a large man hooded against the cold, saw me as I came back to the Christmas tree and struck up a conversation.

I told him I came down mainly for Glenn. This guy hadn’t been there that day–by the grace of God. He immediately got it. “It could have been me, man. You just never know.”

On a June morning in 2006 Jay helped dedicate the memorial wall. He called it “nothing short of a statement to the world that in this city and country we value life. We value courage. We value honor and we honor those who sacrifice for others. We are at once compassionate and resilient. We are principled. We survive adversity and then we flourish.”

Fifth excerpt:

His fiddle told the story

Fifty years later, the violinist picked up a faint smell of horses inside the old synagogue. It was as if particles of hay and sweet grains lingered with oiled leather, drifting in dust as he moved through the beige-colored galleries. A taint of ammonia from urine seeped through what had been a lime-covered floor. Herwig Strobl could almost feel their warm breaths.

In one sense Strobl might have been considered an interloper, a voyeur at the Izaak Synagogue, a Baroque-era building in Kazimierz. The Austrian was the son of a Nazi party boss, a child just four years old when the war ended.

He grew up in Linz, and as an adult became uncomfortable with the secrets and denial embedded throughout the hardened Mühlviertel region. An accomplished composer and performer, he came from a family of musicians and teachers, at first following the course that had been set for him.

When Strobl’s father returned from an American prison a few years after the war, he started a family orchestra: nine-year-old Herwig was told to learn the fiddle, while his three brothers played other strings and drums, and their mother a harmonium. Their repertoire included songs from popular Viennese operettas whose composers fused waltzes with Hungarian folk songs, including so-called Gypsy folk dances. While he didn’t know this as a boy, the sound that Strobl grew to love most closely resembled the instrumental music dear to Eastern Europe’s Jews.

This was klezmer, Yiddish folk tunes.

As a man in his forties switching his life on to a new track, Strobl dedicated himself to playing their music. He felt deeply touched by both the sadness and happiness in the tunes, and by a parallel sonorous sweep in his country’s history. He began introducing audiences to an enigmatic chunk of a culture that had been threatened with burial. While classically trained and a longtime member of the Linz Chamber Orchestra, Herwig took to the streets, busking on plazas and joining music festivals. He formed his own ensemble with a guitarist and an accordion player, performing his interpretations of songs across the continent. And while first immersing himself in klezmer, Strobl also began telling some of his family’s story, and gathering those of other Linzers.

Strobl thought, My goodness, I must do his songs.

One night in 1994, a thin, bearded hippie with a greying ponytail approached Strobl after his trio gave a concert in Kraków. Herwig found Bernard to be incredibly open; it was as if they had been longtime friends. Bernard suggested he go experience the acoustics at the Izaak Synagogue. Although Offen had never worshipped there as a child, he had seen the recent restoration inside, with scrubbed frescoes of Hebrew prayers and symbols on its walls below soaring vaulted ceilings. Most acutely though, Bernard had heard something extraordinary in the halls, a reverberation of sound that took seven seconds to complete. Showing his first film there to small audiences around that time, to whoever wanted to see it, or sometimes just him and a girlfriend, Offen remarked on the delayed echo effect.

It was as if Bernard had introduced his new friend to a fresh muse, setting him to work. “For me it was an inspiration for poetic remembrance of old Jewish life and worship, and it sparked my imagination,” Strobl explained years later. “What I would share in the process of remembrance that Bernard had given to so many people.”

Entering the synagogue Strobl was transported to the prolific Krakóvian bard, Mordechai Gebirtig. He considered the people who had once worshipped there. Like Offen, he questioned, Who were the members? Where did they live? Did they survive? “This kind of building does not come out of nowhere,” Bernard told him.

He thought, My goodness, I must do his songs. Strobl went deeper, contacting a collector of Gebirtig’s music. He began practicing in a modern church in Linz with acoustics similar to the synagogue. Following a concert in Aachen, Germany, he asked violinist Falk Peters to replicate a custom violin called a Braccioline d’amore, which Peters had made for himself.

He introduced audiences to an enigmatic chunk of a culture that had been threatened with burial.

With its five strings and an additional sixth resonant one, the Renaissance-era instrument produced an uncanny deep timbre, an elongated voicing that would stretch even further in the synagogue’s sound chamber. Notes were suspended and dipped quickly like groups of tiny shore birds hanging and darting in the wind, phrases hummed and crackled along the walls.

After a year Strobl thought he was nearly ready to return to Kraków. But his son, Axl, a sound engineer, said not quite. Dad, you’d better practice a half-year more.

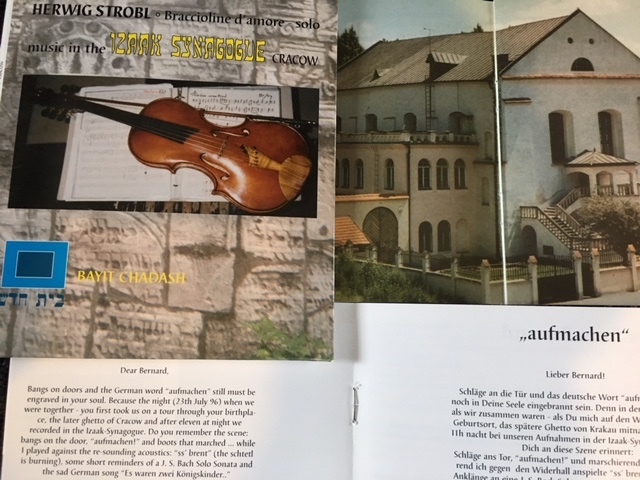

Cover and inserts from Austrian violinist Herwig Strobl's CD, "Braccioline d'amore -- solo music in the Izaak Synagogue Crakow," 1995.

Bernard and Herwig were unlikely collaborators only in a superficial sense. While playing hundreds of concerts, Strobl’s appreciation of klezmer was infused both by guilt for his nation’s sins and a drive to purge his own sense of having been “kept dull” for forty years. Unlike in Germany, which he saw facing its past with determination, attempting to make amends for moral and psychological wounds while educating new generations, he found that many Austrians had ducked their own responsibility. Perpetrators remained almost everywhere, processions of those who had marched well inside the outer ring of indifference. Yet his government’s policy had been neglect and denial, as what Strobl called “the Kurt Waldheim syndrome” had revealed, referring to the former United Nations Secretary-General who lied about his role as a Wehrmacht intelligence officer. Among his countrymen, the only true victims were the descendants of men like Waldheim and his own father. Herbert Strobl, while a talented cellist and pianist, had been at minimum a witness to the burning of villages in Ukraine.

Herwig had taught secondary school in a district shadowed by the former Gusen and Mauthausen camps. Yet no one, none of his colleagues or the townspeople, seemed to talk about the years of destruction and exclusion. The grey Danube froze over in a vast silence. Around this time his father warned Herwig not to get involved with a young woman who had told his son that she was Jewish, saying she “would never come into our clan.” Upon meeting her again sixteen years later, Strobl apologized for having cut off their relationship, and the woman told him she had been joking about her identity. He could not shake off the “joke” as he cut ties to the church, got divorced, and felt cast off by his family. Herwig went further into the folk tunes and traveled to Israel.

“Was I successful in the respect of reaching other people’s hearts?”

Also a writer and a poet, Strobl published a book of stories told by people in his region who finally unburdened themselves. Some of his family’s once unutterable paradoxes emerged as well. While his father had completely embraced Hitlerism, the SS at Hartheim Castle euthanized two aunts who suffered mental breakdowns, half an hour from his home, one of most hideous scenes of mass extermination of both civilians and POWs. The remote former asylum for imbeciles was converted into a killing mill for perhaps thirty thousand handicapped and so-called mentally ill people, in addition to those victims from Mauthausen and its sub-camps. His aunts were gassed in the same chamber where some of Sam and Nathan Offen’s workmates died. Herwig spent a night in the former doctor’s quarters there, wanting to know what it felt like sleeping where a murderer had lived—around the same time Bernard stayed overnight in the commandant’s office at Auschwitz. Later Strobl produced music for a play about the atrocities at Hartheim.

His fiddle told the story, his playing burst open a channel. It brought some audiences to an intersection of melancholy and gay, crossing between each in “a symbolic attempt to right wrongs.” Penetrating recesses that language fails to reach, the music ushered in at least a momentary connection with the very traditions, the same oscillating life, that many of their relatives and neighbors had tried to wipe out.

Sometimes tossing a shock of frosted hair as he strummed, Strobl urged his audiences to go further. His bow scratched and plucked high on the frets, he soared in streams and doubled back, he broke into minor keys, casting allusions to Johann Strauss and J.S. Bach, all the masters he had grown up with.

Knowing that words have gaps and are easily misinterpreted, he realized that by just playing, inside the music you can relate and tell it again. Always my idea was, it’s necessary to transport the idea of the song and the background of how I got to the song, and the stories people want to know, and the experience.

At seventy-five years old, he questioned his own reach. “Was I successful in the respect of reaching other people’s hearts?” Strobl wrote me in 2015. “Did Austrians change their minds to become more aware and more empathetic?”

Here is an excerpt from Closer By The Mile the story of the Pan-Mass Challenge bike-a-thon for cancer research, published in 2013:

One day Sandy Fitzgerald was out walking with her amber-eyed granddaughter. She asked Hannah: “Do you think we’ll ever take life for granted again?”

“Grandma, never,” she said. “Never, ever.”

When she was seven, right around Thanksgiving Hannah Hughes just wasn’t herself. She was stuffed up and felt tired. A pain in her legs brought complaints, which was unusual. That Friday, when Sandy and her husband had Hannah and younger sister, Fiona, overnight, which is their tradition after the holiday, Hannah barely wanted to hang popcorn strings on the fresh Christmas tree. She’d recently asked Sandy to carry her bags in school. Her parents thought it might be a nagging sinus infection. Dark circles seemed to brood under her eyes, and her eyelids were a strange red. Hannah had black and blue marks all over. Tears rolled down her eyes as Hannah slept beside her grandmother.

Hannah Hughes, right, with her sister Fiona, who donated bone marrow 16 months before to her sister, in their driveway in 2012.

When Jeff Hughes took his oldest child to the doctor the next Monday, they found an enlarged spleen and a white blood cell count that was through the roof. Her mom Rana was teaching a third grade class when the principal walked in. Your husband, he said, needs you to call.

Hannah was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. In just a few hours she was admitted to Albany Medical Center and began chemotherapy.

She has a rare genetic abnormality called the Philadelphia Chromosome-positive ALL. Having the chromosome makes one more susceptible to uncontrolled division of white blood cells that cause the disease. While not everyone with the Philadelphia Chromosome has positive ALL, children with positive ALL face an even higher risk of dying than those with some other forms of leukemia.

She endured three rounds of treatments through that first winter. Then she underwent a successful bone marrow transplant with a donation from Fiona, who was five at the time. As Hannah’s health inched forward there were months of near isolation, starting with 40 days in her room at Boston Children’s Hospital, to avert any virus that might attack her depleted immune system. Then came a long rotation of checkups with her oncologist close to home in upstate New York, and sometimes driving to the clinic at Dana-Farber.

Hannah endured other trials similar to what many children with cancer face: a grueling rotation of immunizations and intravenous antibiotics, cut off from friends and school life, all while facing the unknown.

A knot still tightens within Jeff and Rana as they await a blood cell count, though not quite so taut as in those early months. At one time they dreaded any infection that might compromise her transfusion line. And putting in the double-lumen catheter line during that first week was harrowing. Their brown-haired daughter was emaciated at less than 50 pounds. The surgeon doubted he could do it, as Hannah’s blood vessels were so tiny. He took off his mask, his face exhausted and creased. For an instant Rana thought the worst, the oncologist demanding, “You have to get it in.” Twenty minutes took four hours. Yet the line held. “We owe him a huge debt of gratitude,” her mom now declares.